|

In any sport our dogs compete and train in there is always a potential for injury. The sport of agility, however, has a high degree of physical challenge and with that also comes a higher risk of injury. As a canine physio, my personal view is that an active lifestyle far outweighs the potential risk of an injury. One key part of injury prevention is becoming aware of the potential injuries your dog may experience in their sport as well as aspects of the sport (e.g. certain movements or obstacles) that are known to cause more strain on the dog’s body. Knowing the potential injuries of the sport means we can better prepare our dogs to avoid injuries and begin to recognize the signs and symptoms of an injury while it’s still in the early stages. This is critical as it’s not always obvious that our dogs are hurt or injured. With any high drive sport, particularly in agility, it is often very subtle signs that point towards an injury rather than something obvious or dramatic (e.g. severe limp). Our dogs have a lot of heart and love for the game and slowing down (due to pain or discomfort) does not come naturally to them. When their adrenaline is spiked, these dogs can push through anything! Although this may be desirable from a performance standpoint, it is can make injury identification far harder!! In Part Two of the Agility Sport Breakdown, we will review the obstacles and movements that cause more strain on the agility dog and then review potential injuries and the common signs and symptoms of these injuries. What Puts the Most Physical Stress on our Agility Dogs??In Part One of our Agility blog series, we reviewed the physical requirements of the sport of agility. Physically, agility is a challenging sport and there are certain maneuvers/obstacles that cause more strain on the dog when they are training or competing. It is important to be mindful of these factors when playing this game as this can play a huge part in injury prevention! A few stressors might include:

All these factors listed above can cause strain on our agility dogs especially when done at high speeds. As the sport grows in popularity and in an effort to improve the safety of our agility dogs research into agility-related injuries has steadily grown. A study, which looked at 3,801 agility dogs worldwide found that roughly 1/3 of dogs participating in the sport sustained an injury. About 42% of the injuries were attributed to jumping (16%), the A-Frame (14%), and the dog walk (11%) (Cullen 2013). The Cullen study also found that Border Collies, one of the most popular breeds of the sport, were 1.7 times more likely to get an injury. This could be due to the speed, arousal levels, and quick directional changes Border Collies are capable of. The study also found that more experienced dog and handler teams had reduced odds of injury. As dogs age and grow in their partnership with their handler their skills and accuracy will improve. In Part Three we will review in more detail how these factors affect our dogs but it’s important to recognize and identify the areas in the sport that put the most strain on our dog's body. With this knowledge, you can better plan your training sessions and make adjustments to the number of repetitions, the surface you train and compete on, or the amount of training you do in a day or given week. Many of the factors discussed are the leading causes to some of the common agility-related injuries I see in my own clinic. With that in mind, let's take a closer look at what some of these injures are, how they can occur, and how to recognize them in your dog. Common Injuries in the Agility Dog 1) Muscles Strains Muscle strains are one of the most common injuries seen in sport. In fact, of the 3,801 dogs in the Cullen study found that 32% of agility dogs suffered from some kind of orthopaedic lameness during the course of their training and 53% of the lameness was caused by muscle or tendon injuries. Soft tissue injuries (strains, sprains and contusions) to the shoulder, back, phalanges and neck were the most common types and sites of injury (Cullen, 2013). Further research has revealed that 32% of hind limb lameness involved the iliopsoas muscle group (Carmichael, et al 2012). A muscle strain is an injury to a muscle or a tendon. Typically, muscles are strained when they are in their fully lengthened or elongated state and are over stretched. Muscle strains can occur for a number of reasons in agility including:

The iliopsoas muscle is one of the most common injured muscle in the agility dog. The iliopsoas is a muscle group comprised of the psoas major and iliacus. The main function of this muscle is to act as a hip flexor and also works to internally rotate the femur. This muscle is typically injured when it is lengthened and on a full stretch (hip extension). In the sport of agility, dogs spend a great deal of time in hip extension and can injure this muscle from:

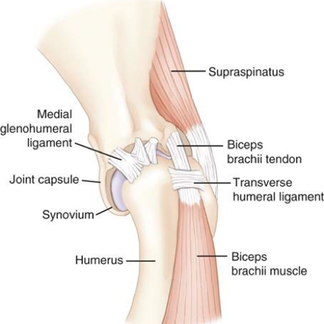

2) Medial Shoulder Syndrome Ridges Referrals (https://www.ridgereferrals.co.uk/pet-owners/factsheet/shoulder-injuries-in-dogs/) Ridges Referrals (https://www.ridgereferrals.co.uk/pet-owners/factsheet/shoulder-injuries-in-dogs/) The shoulder joint is one of the least stable joints in dogs and relies primarily on tendons and muscles for support. Unlike humans, our dogs do not have a collar bone and rely on the surrounding muscles and ligaments to hold their shoulder together. Medial Shoulder Syndrome (MSS) is an injury that agility dogs can experience. The medial shoulder is comprised of the medial gleno-humeral ligament (MGL), the joint capsule, and the subscapularis tendon. These play a vital role in stabilizing the shoulder and acts as an emergency brake, especially when the shoulder is placed into abduction (out to the side, away from midline). Repetitive jumping, hard and tight turns, and weave poles place the shoulder near its end range of shoulder abduction, stressing the tissues of the medial shoulder complex. The exact cause of MSS is unknown but it's thought to be more related to chronic repetitive activity and overuse versus trauma. An injury to the medial shoulder structures can result from:

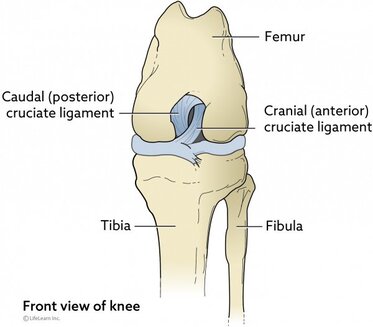

3) Cruciate Injuries A cruciate injury can be a devastating injury to the agility dog. The knee (or stifle joint) is made up of the cranial and caudal ligaments. These two ligaments are bands of fibrous tissue located within each knee joint. Cruciate, meaning “to cross over” or “form a cross” plays a key role in ensuring the knee works as a stable hinged joint. The cranial cruciate ligament is responsible for the forward stability of the tibia and is the most often torn or severed. The caudal ligament, which is slightly thicker and longer than the cranial ligament is responsible for the backward stability of the tibia. More often than not, dogs injure the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL). CCL injuries are often a result of an underlying issue that has been brewing for a while versus a single traumatic event. Common causes of the CCL include:

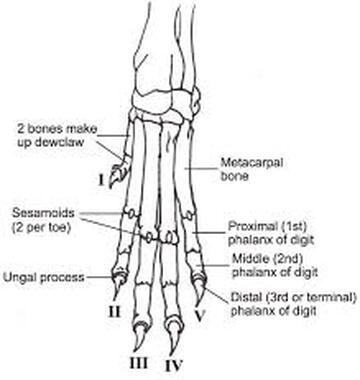

A CCL injury can take almost a year to heal. A study of agility dogs with CCL tears treated with a TPLO surgery found that the average time for a return to sport post-surgery was 7.5 months (Heidorn 2018). Having a rehabilitation plan and a proper return to sport program will help to get you and your canine companion back in action and reduce their chances of future injury. 4) Toe Injuries With all the physical demands of agility, it may come as a surprise to learn that toe injuries are a common area for agility dogs to experience an injury. When looking at a dog's foot the toes that make contact with the ground are essentially the pinky, ring, middle, and index fingers - the dewclaws, located higher on the leg are like the thumb. When standing, the front dewclaw may not appear to be functional because it doesn't come in contact with the ground but observing the dewclaw when the dog is in motion tells a different story. Five tendons attach to the dewclaw and play an important role when the dog is in motion. For example, when a dog’s lead leg is on the ground during the gallop or canter, the dewclaw is on the ground to stabilize the carpus. Additionally, when a dog turns, the dewclaw digs into the ground to support the structures of the limb and prevent torque. Previous research has thought that our dog’s third and fourth digits were the most important due to their central location within the feet and due to their length in comparison to other toes but research has shown that substantial weight is also placed on the fifth pad and on the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal pads (Sellon et al. 2018). The 2018 study found that digit injuries were more likely to occur in the front limbs (P< 0.001) than hind and that digit 5 (the outside digit) was the most frequently injured while the dewclaw (digit 1) was the least frequently injured. The researchers suggested that forces applied when dogs are turning at high speeds on the agility course may act as repetitive stressors to digits 3, 4, and 5 and that these digits may be of more importance to athletic function than previously recognized. The results of the study also suggested that the removal of the dewclaws in the forelimb may be a risk factor for injury to other digits. The front dewclaws may have a function in preventing torque on the limb, and as such, the removal of dewclaws may predispose the dog to injury (Sellon et al. 2018). Speaking with agility competitors about toe and carpal injuries many would identify the A-Frame as a likely suspect. However, a study on the A-Frame performance of agility dogs found that regardless of frame angle to the ground, the dogs' carpi always extended to about 62 degrees. The authors compared this to dogs walking (26 degrees), and in dogs traversing a jump (44 degrees). Repetitive maximal carpal extension could damage soft tissue structures. However, Chris Zink DVM argues that the degree of carpal extension is not out of the ordinary for dogs. Looking at dogs cantering or galloping the carpal angles was about 64 degrees (Zink 2018). Dogs ascending a frame were experiencing carpal extension that is normal for galloping dogs. While you may think that the A-Frame is the prime culprit of toe injuries the research suggests that this doesn’t appear to be the case! One this to consider is the force of impact your dog in their shoulders may experience when coming down the apex of the frame. While this may not lead to a toe injury the A-Frame performance could contribute to injuries or soreness in other areas of the body. What are the common signs of a toe injury?

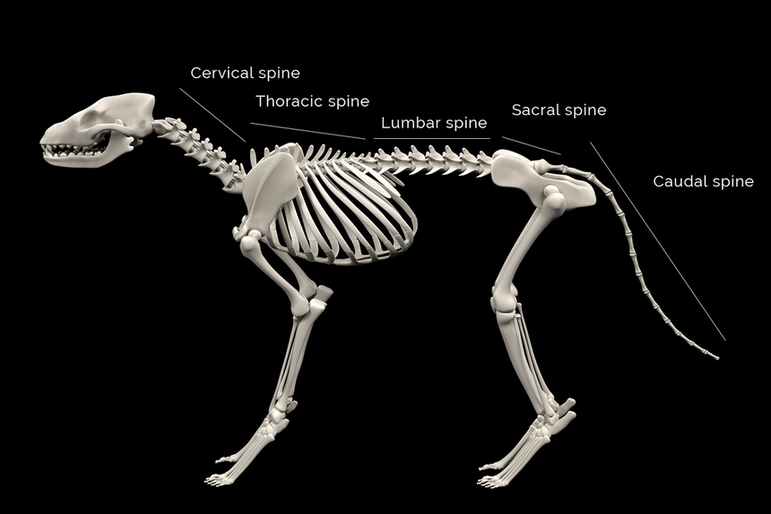

5) Back / Spine InjuriesOur dogs' spine is a complex system made up of a series of small bones called vertebrae which forms a tube to protect the spinal cord. The spinal cord is a vital part of the central nervous system responsible for carrying information from the brain to other parts of the body. Canine's have 7 cervical (neck) vertebrae, 13 thoracic vertebrae, 7 lumbar vertebrae, 3 sacral vertebrae, and a variable number of caudal (tail) vertebrae. Vertebrae connect to each other through two joints – discs and facet joints. Discs are the cartilage cushions between the vertebral bodies. Each disc has a thick fibrous outer rim (annulus fibrosus) and a soft jelly centre (nucleus pulposus) as well as a cartilage cap on each side that joins it to the bone. Facet joints are small synovial joints between the vertebrae that allow the spine to bend and flex. They also assist with load transmission. We then have multiple layers of muscles to help support the spine and minimize concussive forces. Back injuries can vary in severity from mild to serious. They can occur from:

What are the common signs of a back injury?

If you have a dog with a long back or if you suspect your dog may be at an increased risk of a spine injury or issue then it’s important that you choose activities that don’t put their spines at increased risk. This may mean you’re opting to have your dog jump at a lower height or that you’re limiting the number of repetitions of sequences or equipment you ask of them. In conjunction with spine issues, your dog may sustain an injury to their sacroiliac joint (SIJ). Have you ever heard from your health professional that your dog’s pelvis has “gone out?” Often when your health care provider says this, they’re referring to an issue of alignment in the pelvis. Pelvis asymmetry can be a primary or secondary issue, meaning, it can be main issue or compensating for another injured area (e.g. spine/iliopsoas/CCL issue/tight muscles). The SIJ or pelvis can have similar signs of discomfort as the spine. Common signs of an SIJ dysfunction might include:

If your dog has ongoing pelvic issues then regular visits to a qualified health professional for proper diagnosis and treatment is necessary. Pelvic mal-alignment is often due to poor stabilization of the smaller muscles or from tight muscles. The pelvis can also be affected by excessive twisting, collisions, slips and falls, or overuse from compensating from another injury. Remember, that the pelvis is very much a part of the spine and if your dog’s pelvis is out their spine should also be checked out. It is also important to determine which of these is primarily contributing to the problem for problem rectification. If you are routinely having your dog’s pelvis adjusted, then it’s time to consider the strength of their stabilizer muscles which help hold everything in place. A conditioning program that focuses on strengthening of the small stabilizer may be necessary to address the underlying issues of the pelvis. ConclusionInjury is a fact of life and chances are at some point in your dog's sporting career they will suffer an injury. Our dogs are hardwired to hide both illness, injury, and signs of discomfort so if you are ever worried that something may be wrong or off then don’t hesitate to reach out to your health professionals. Even a minor injury, left untreated, can develop into something that lingers or balloons into something more serious. Remember that you know your dog best and to always follow your gut! In my clinic, it’s often the subtle things we notice – such as a poor foot placement or difficulty maintaining position that are clues to an underlying issue or weakness. By the time our dogs are really showing signs of lameness or obvious discomfort that the injury is more progressed and more difficult to treat and manage. Regular health checks are a must for the agility dog! Having a health professional regularly put their hands on your dog and getting regular “tune ups” is crucial to their health, fitness, and performance in sport. We wouldn’t expect professional athletes to avoid regular health checks from their physio, massage, or chiro teams and the same is true for our sporting dogs! My preferred method for treating an injury is to be PROACTIVE and not REACTIVE. This means we want to work towards preparing our dog to meet the physical demands of the sports and activities they do! In our next blog, we’ll continue to breakdown the sport of agility with a closer looks at how we can prevent injuries BEFORE they occur. Sources“Canine Cruciate Ligament Injury” Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/vth/small-animal/sports-medicine-rehabilitation/Pages/canine-cruciate-ligament-injury.aspx

Balkman, Rachel. “Conditioning for Deceleration.” Sport Dogs January 28th 2019. Canapp, Sherman O. “Returning to Agility Competition After Treatment for Medial Shoulder Syndrome.” Clean Run Carmichael, S. Marshall, W. (2012) Muscle and tendon disorders. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA, eds. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 1127-1134 Cullen KL, Dickey JP, Bent LR, Thomason JJ, Moëns NM. Survey-based analysis of risk factors for injury among dogs participating in agility training and competition events. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013 Oct 1;243(7):1019-24. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.7.1019. PMID: 24050569. Edge-Hughes, Laurie. “Assessment and Treatment Techniques for Canine Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunctions.” https://fourleg.com/media/Canine%20SIJ%20notes.pdf Heidorn, Shannon, and Sherman O. Canapp Jr,Christine M. Zink, Christopher S. Leasure, Brittany J. Carr. “Rate of return to agility competition for dogs with cranial cruciate ligament tears treated with tibial plateau leveling osteotomy,” JAVMA (2018) | 253: 11, https://www.vosm.com/uploads/772c17ed-5af3-4744-9fe1-089ee29e129e-CCL%20Return%20to%20Agility%20JAVMA.pdf Mitchell, T (2017). How to be a Concept Dog Trainer. Westline Publishing Limited, United Kingdom. Pastore C, Pirrone F, Balzarotti F, Faustini M, Pierantoni L, Albertini M. Evaluation of physiological and behavioral stress-dependent parameters in agility dogs. Journal of veterinary behavior. 2011;6(3):188-194. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2011.01.001 Sellon et al. (2018). A survey of risk factors for digit injuries among dogs training and competing in agility events. J Am Vet Med Assoc; 252(1):75–83 Zink, Chris. “A-Frame Induced Carpal Injuries,” For Active Dogs. 1:7 (2018) https://myemail.constantcontact.com/A-Frame-Injuries-.html?soid=1129243778926&aid=XhRMy3-hMNM

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCarolyn McIntyre Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed