|

Agility is a fast-growing and popular sport that has taken the dog world by storm! Popular with both pet owners and competitive dog trainers', agility is an inclusive sport open to all dogs and handlers of different shapes, sizes, and abilities. Agility first appeared as a filler spectator sport at the Crufts Dog show in the United Kingdom in 1978. The sport has its origins in horse show jumping and was officially recognized by the kennel club in 1980. National agility clubs like the Agility Association of Canada (AAC) and United States Dog Agility Association (USDAA) began to appear in the early to mid-1980s. Since then, agility has become the fastest growing dog sport in North American and around the world.

In this sport breakdown, we will take a look at the sport of agility! There is so much to cover for this fast and fun sport that for the first time ever we’re splitting our sport breakdown into FOUR parts! In the first instalment of our agility series, we’re taking a deeper look into what the sport of agility is and the physical demands it places on our dogs. Then, in Part Two, we’ll review the potential injuries that can occur and a few common signs and symptoms that owners should watch out for. Part Three will highlight what YOU can do from an injury prevention standpoint to help keep your agility dog off the sidelines. Finally, in Part Four, we’ll look at the role of canine conditioning for our agility dogs, why we should be conditioning our dogs, and what we should be including in a conditioning program tailored to the agility sport dog. What is Agility?

Agility is a sport that includes the owner (aka handler) directing the dog through a predetermined obstacle course of 14-20 pieces of equipment including jumps, tunnels, weave poles and contacts (A-frame, teeter, and dog walk). The handler will navigate the dog through the course using both body language and a series of verbal commands.

In agility, there can be a number of different courses a dog may be asked to compete or “run in”. In Canada, the main type of course is called a Standard course which includes jumps, tunnels, contact equipment, pause table and weaves. Dog and handler teams attempt to perform the course with speed and precision under a standard course time and without acquiring any faults. Faults can result from knocked jump bars, taking the wrong obstacle in the sequence, refusing or missing an obstacle, failing to touch a “contact zone” of an obstacle, or going over time. Organizations will also have “Game” events that you can run with your dogs. Games have their own unique set of rules and challenges. Some games will have limited types of equipment and may emphasize speed and accuracy, while other games may include distance challenges.

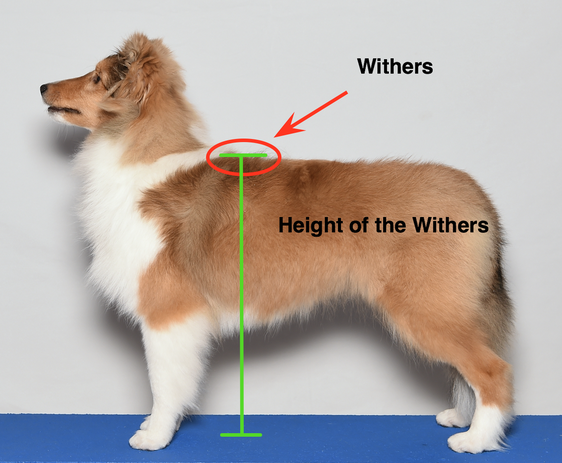

In agility, dogs are placed into categories or “classes”. All dogs start in a Novice/Starter level and progress through to Advanced/Intermediate level, and then Master/Excellent level. Depending on the organization, dogs will need to qualify with a certain number of “clean” or qualifying runs before they can move into a higher level. Typically, the Starter/Novice level has fewer obstacles, less challenges and longer allotted course times. As dogs work through their levels, the challenges become more difficult. After the dogs enter the Masters/Excellent level and achieve that title, they can work on earning additional championship titles which each have their own unique requirements. Agility is a sport where dogs of different ages and abilities can compete. In order to compete, dogs must be 15 to 18 months of age at the time of competition. This minimum age requirement will vary based on the organization. This requirement was designed with the dog’s safety in mind so dogs are not competing until they are physically mature. In competition, dogs are put into a height class to compete against dogs of a similar size. The dog’s jump height is based on the height of the dog’s withers.

Each organization will have different jump height categories that range from 4 inches to 26 inches. Dogs can also compete in Special or Veteran classes which allows for lower jump heights and increased time for dogs who are older or require lower jumping heights. In these special classes, often times the double and spread jumps are removed and the A-Frame is also set to a lower height. As a popular and ever-growing sport, dog agility has a number of organizations that run in both Canada and the United States. In Canada, some of the larger organizations are :

In the United States, some of the organizations are:

Dogs and handlers can also compete at the international level as well. Different national organizations will send teams of dogs and handlers to one of four World Organizations to compete. The CKC and AKC will send delegates to the Federation Cynologique Internationale (FCI) World Agility Championships (WAC). The (FCI) is the parent body that governs and standardizes Kennel Clubs and purebred dogs around the world and some mixed breed dogs may be barred from competing at the WAC. National teams may also send dogs to the European Open, which is open to both mixed bred and our purebred dogs. The Agility Association of Canada will send a Canadian team to the International Federation of Cynological Sport (IFCS) to compete. The fourth and final international organization is the World Agility Open (WAO) which the UKI Agility Club will send teams to compete.

The Physical Demands of the Sport of Agility

Agility has a number of physical challenges that any dog, whether the dabbler or international competitor, should be prepared to meet. As course designs and handling techniques have evolved, the sport of agility is becoming increasingly more physically demanding for our canine companions. Handlers are seeing tighter turns, faster overall speeds, more complex jumping skills, and challenging contact and weave approaches. Agility requires the dog to move in all three planes of motion and includes a variety of dynamic movements (at speed) that can potentially lead to an injury. Although we may see more speed and accuracy with dogs competing at a higher level of training or competition, the physical requirements of the sport are the same for training at all levels of competition. As a canine physio, I often stress to my clients the importance of examining the physical challenges of any sport they choose to do with their dog. With a clear understanding of the challenges agility places on our dog’s bodies, you can better plan their training, conditioning and lifestyle to ensure they are physically able and safe to participate in the sport. There is always a risk of injury when participating in any sport (dog or human), however, by better understanding the physical requirements, you can set your dog up for success with a long career in this exciting sport!!

Let’s take a look at the physical requirements of an agility dog. 1) Explosive Power Gallifrey leaving a start line (Kayla Grant) Gallifrey leaving a start line (Kayla Grant)

I find there is confusion between what is power and what is strength!! Guess what? The agility dog needs both and each have their own distinct characteristics. When we talk about power we’re really referring to the ability to produce as much force and velocity in a short amount of time. Strength, on the other hand, measures how much force your muscles can produce. Power is essentially a combination of strength and speed. The faster your nerves can recruit muscle fibres, the more power your dog will have!!

Explosive power in agility will help to improve your dog’s course times, as they will be able to cover more ground with less strides making them far more efficient. Without sufficient power, dogs take more strides and will run slower. Power is also needed to accelerate and explode forward out of a tunnel, a turn, over a jump or regaining speed after coming off the contact equipment. Explosive power is also critical when your dog comes out of their starting position. At the beginning of an agility run dogs are often asked to sit, lay down, or stand in a stay /wait position while the handler gets themselves into position (aka leading out). By leading out, the handler has the opportunity to get into position to direct their dog to the next obstacle on the course. The dog, once called by the handler, will have to explode from this stay and quickly get up to speed to perform the first obstacle. Researchers are currently investigating which starting position will yield a faster time off the start line. It is hypothesized that the down position may bring the dog up to full speed faster as the dog is utilizing both their hind end to power out of the down as well as their front end to propel forward. This combined approach is thought to be faster versus exploding out of a sit where the dog primarily powers from their hind end with little front-end involvement. Although the down “could” be considered faster off the start line, the risk of increased pull/force on the dog’s front end is certainly a consideration! Stay tuned as we wait for the research to unfold. 2) Overall Strength

The sport of agility requires your dogs to have excellent overall strength to allow them to safely perform each obstacle. It is simply not enough to only complete your sport specific training skills at your weekly class – I cannot emphasize this enough!! Consider a human athlete. They don’t just focus on their sport specific training but combine cross training and conditioning to improve their performance. Given that your dog moves dynamically in this sport, strength is required in all areas of the body – front end, hind end, and core!

There are two different groups of muscles we want to focus on strengthening in our dogs - the prime movers and stabilizers. The prime mover muscles are typically larger than the stabilizers (e.g. quadriceps, hamstrings, biceps, triceps) and are responsible for moving the body! These muscles connect to the bones via tendons and create the specific movement around a joint. The stabilizer muscles, as the name would imply, help to support or “stabilize” the body. These muscles are instrumental in maintaining proper form and positioning, preventing pain, and decreasing the risk of injury. When the body has weak stabilizers, it becomes more difficult to perform tasks because of improper alignment and positioning. Furthermore, it can cause pain as misalignment strains joints and tendons unnaturally and unnecessarily. The strength of the primary movers doesn’t matter if the stabilizers are not strong enough to hold the limbs exactly as desired or support the joint during powerful athletic movement. A powerful limb that cannot be controlled with equally powerful stabilizers will lead to wobbliness, weakness and inefficient movement. We always want to make sure we are strengthening all parts of our dog’s body – front limbs, hind limbs in various directions to help support functional movement. One area in particular that we will want to strengthen is our dog’s front end, also known as our dog’s braking system. The front limbs are also responsible for:

The concussive forces of repetitive jumping on a dog’s front end can cause issues over time (Pfua, 1997). The study found that vertical force was observed in the forelimbs (4.5 times bodyweight) when landing from a jump at high speed. Now think of how many times your dog might land after a single agility training session or event? The A Frame can also present a challenge to your dog’s front end. From a physiological stand point, the 2 on/2 off method places the most strain on the dog’s shoulders compared to running contacts. The steeper the A Frame is, the more vertical your dog’s body will be when performing the 2 on /2 off contact method placing higher strain on the front end assembly. By having a strong front end, we add critical support to the tendons, muscles, ligaments and joints to minimize overload and strain. Another area that will need consideration for strengthening is the dog’s hind end. The hind end is considered the propulsion mechanism (pushing forward) of the dog. In agility, your dog’s hind end helps with jumping power, speed, accelerations from stops or changing directions. A well strengthened hind end will also allow for more effective functioning of the front end. Finally, the core function comes into play in all aspects of movement. Core strength refers to the control of the muscles that support the spine e.g. abdominal muscle, obliques and the muscles in the pelvic area (e.g. hip flexors). These are critical muscles that function to align, stabilize and move the trunk and the spine especially when working in a dynamic fashion!! The core also supports the back muscles allowing the pelvis, hips and lower back to work together smoothly. Lack of core strength can lead to inefficient movement patterns which can cause your dog to overcompensate by overusing other muscle groups – this increases their vulnerability to injury. In agility, core strength can also help to keep the limbs IN the air while jumping (versus slipping down and knocking a bar) and improve your dog’s jumping mechanics. Overall, strength will not only improve your dog’s performance in agility (e.g. speed, endurance, power) but will also prepare them for the other activities they enjoy outside of the sport. It is also a key physical requirement for longevity in the sport. 3) Weight Shifting to the Hind End

Teaching our dogs how to properly weight shift back and engage their hind end is a critical physical requirement in the sport of agility. Our dogs are front-wheel driven with 60 per cent of their weight resting in the front end and 40 per cent in the hind end. Dogs are faster when exploding off from their rear end (which requires weight shifting to the hind end) versus pulling from their front end. Remember, the power house of the dog is the hind end! Less power is created from the front end and because of the natural tendency for dogs to carry more weight in their front, it can be a HUGE potential for injury if the reliance is on front end structures to accelerate forward. Learning to weight shift can be easier said than done! Age, learned behaviours, rear end injury or chronic conditions, repetition of forward weight shifting, arousal level, training, slippery surfaces, losing balance, and handler position can cause your dog to place more weight on their front end. Dogs will often take the path of least resistance, so it can be easier and more natural for them to load their front end. Given that a dog is already front wheel driven, teaching them how to incorporate and use their hind end effectively will minimize potential injuries, especially to the dog’s front end!

Effective weight shifting to the hind end will also help improve our dog’s jumping, ability to collect and extend/accelerate and turning ability. Weight shifting will also assist the dog with completing their contact obstacles. Ascending the contact equipment will require not only weight shifting but hind end strength to propel them upwards (versus relying on the front end to effectively pull the dog up). It also becomes important when descending the equipment, especially if the dog assumes a 2-on 2-off contact position. As previously discussed, the 2 on/2 off contact method will place more stress on our dog’s front end so by teaching them to weight shift back, they are actively reducing the strain on their front end. 4) Flexibility

Flexibility refers to the joints and muscle’s ability to move through a full range of motion. Our dog's bodies are broken down into three different anatomical planes – median /sagittal (movement forward and backward), dorsal (bending movement), and transverse (twisting or rotation motion). In the sport of agility, our dogs move in and out of all three planes of movement. Dogs have to contort themselves, twist, turn sharply, and navigate challenging jumps at speed. This requires their muscles to be flexible, lengthened and stretched to avoid the risk of injury. A well-stretched muscle can also attain full range of motion much easier which will improve your dog’s athletic performance.

When a muscle contracts repetitively over time and is not stretched back to an elongated or lengthened position, the muscle will begin to tighten and shorten. This creates problems for muscles and tendons! If your dog has shortened, un-stretched or tight muscles, they will create less power in their movements. Not only can this cause slower speeds, but can create a cascade of weakness in that muscle that is difficult to overcome if the shortened position of the muscle persists. A weakened muscle that is asked to do more work than it is able is a recipe for a muscle injury! The flexibility of the dog becomes critical when your dog is completing a turn. An inflexible dog (especially in the spine) will not be able to turn as tightly, creating large sweeping turns. It can also affect your dog's jumping ability. When a dog is going over a jump, they will turn their head to look where they are going next. If they have restricted and tight neck or back muscles, this will alter their turn following the jump and can affect their acceleration when they land. 5) Jumping Skills

One of the key performance components of dog agility is jumping. Our dogs are terrific athletes and jumping is a behaviour that comes quite naturally to them. As jumping is something our dogs do regularly (onto couches/beds, into vehicles etc), we may be tempted to take their jumping ability for granted. As a result, we may not spend as much time teaching our dogs to jump efficiently or safely. Not only is it important to teach our dogs how to jump properly, but teaching them to utilize their body properly while jumping can minimize their chances of injury and/or compensation problems. In the sport of agility, dogs will have to navigate jumps of different types and sizes, heights, colours and angles. These might include winged jumps, non-winged jumps, panel jumps, wall jumps, spread jumps, double jumps or broad jumps. Dogs are required to complete jumps from either the front or back side. They will also be asked to perform these jumps from challenging angles – not all jumps are approached from a straight line! We will also want our dogs to take these jumps with confidence, good mechanics, and speed. When jumping our dogs will also have to be able to judge distance and when to lengthen or shorten their stride to take the jump. Our dogs may also be required to turn abruptly before or after the jump. On top of all that the dog also has to keep the bar from dropping!

In an agility course, the jump is the most common piece of equipment your dog will encounter. A lifetime of jumping in both training and competition can take its toll on a dog – look at the number of jumps a dog has to complete in a weekend of an agility trial – potentially 40-50 jumps on each given day! You can read more about the mechanics of jumping here. As the most common piece of equipment your dog will see in the sport of agility it’s important that you spend time training proper form, mechanics, and build familiarity to the different types of jumps and angles of approach your dog may experience. Remember, avoid taking advantage of their natural affinity for jumping! 6) Balance and Body Awareness  "Look mom! No paws!" A confident dog can move over the dog walk with incredible speed (Down the Lead Photography) "Look mom! No paws!" A confident dog can move over the dog walk with incredible speed (Down the Lead Photography)

The ability to navigate a space and intrinsically “know” where your body is in a space is what we call proprioception. It relies on a combination of information from joint sensors, muscle sensors, visual cues and information from our vestibular system in the ear. Like us, our dogs also have proprioception and it’s this sense that will help them work on various pieces of equipment. As your dog moves, it must continuously monitor its posture and adjust muscle activity as needed to provide balance. Proprioceptors sense these movements and allow fast, unconscious, and accurate execution of these behaviours.

All dogs’ joints contain conscious proprioception receptors. These receptors tell the brain where the body is in space. If we stimulate these receptors to become more sensitive, they can warn the brain faster if the body starts moving in an unusual direction. The brain can then stimulate the muscles to contract and prevent the joints from twisting and being injured. Pieces of agility equipment such as the dog walk and teeter are narrow surfaces that the dog will have to navigate with speed. The dog walk, in particular, is a piece that some dogs can complete with incredible speed – some dogs, like a Border Collie with a running contact can complete this obstacle in under 2 seconds! When our dogs are moving at those speeds, one mis-step can lead to a catastrophic injury. Regardless of what level you’re training at or how fast your dog completes these pieces of equipment, the fall/injury risk is still present. You wouldn’t want to run across a 4x4 that’s a couple of feet off the ground without first learning how to control your body and have good balance. The same rings true for our dogs!! Without body awareness and balance your dog’s movements can be clumsy and inefficient and they can tackle the obstacle with less confidence and speed. For example, for younger, more inexperienced agility dogs, they tend to ascent the up ramp of the dog walk with their feet wider apart. Once they get onto the horizontal plank they’ll bring their feet back underneath their body again (Zink 2018). In some cases, the dogs will spread their feet so far apart their toes will curl over the edge! Our dogs spread their feet to gain a wider base of support to improve stability. When adopting this wider foot set, the dogs have a higher chance of falling off the obstacle. Increasing our dog’s balance and body awareness will help them to gain more confidence in their obstacle navigation and in turn improve their speed of completion. Heightened body awareness will also help your dog move more efficiently, turn quicker, and have improved control of their body and movement patterns, all which will decrease their risk of injury! 7) Ability to Decelerate/Collect

The ability to collect, extend and collect again is not an easy skill for our dogs to learn! The ability for any dog to easily transition back and forth between acceleration and deceleration is a learned skill that will take time to master. Our dogs navigate agility at high speed and will have to be able to collect (aka slow down), turn, and change direction and explode forward with a moment’s notice. As your dog progresses in the sport, they will likely begin to see courses that are more complex with greater handling manoeuvres and changes of direction and speed. Deceleration is a complex physical challenge for our dogs. A strong core and front end will help to effectively slowdown (collect), which helps to remove some of the braking power from the shoulders. A dog that can transition from slow to fast speed and vice versa is a dog that is moving efficiently, quickly, and will be able to manage the challenges thrown at them in the higher levels!

The ability to collect and decelerate is also a critical factor in how your dog performs a jump. If they lack the ability to collect, this will alter their take off point, their angle of elevation, and how they land. For highly driven or aroused dogs, the ability to collect can be challenging!! Without this key physical component, the risk of injury can increase. Not only can this cause more strain on the dog’s front end but can lead to knocked or crashed bars/jumps, unsafe completion of contact equipment, missed weave pole entries and larger/sweeping turns out of tunnels/jumps. 8) Navigate Weave Poles

The weave poles are a challenging piece of equipment that requires your dog’s whole body to work together in order to achieve the designed form, speed, and accuracy. In agility, dogs can be asked to weave 6 or 12 poles. The dog will need to “enter” the poles correctly -with the dog entering from the right side of the first pole. The entry to the weave poles has gradually become more difficult with different angles of approach. Dogs can complete the weave poles using a single leg swimming motion or a double leg slalom motion. In one-sided movement, loads on the individual leg increase as the leg has to quickly absorb the impact of landing and push off to the next stride.

When our dogs are weaving the dog’s spine flexes upon entry to start the weaving motion. Depending on your dog’s style of weave their forelimbs will move in either a one or two-sided action while the centre of the body arcs in the opposite direction. The hind limbs slalom from side to side and create a torque through the mid and lower spine; the tail acts as a router to balance the dog during the motion. Strength in your dog’s adductor and abductor muscle group is critical to support their limbs during weave pole navigation and prevents the limbs from hyper extending or slipping out when completing the obstacle. For more information on the physical challenges of the weave performance visit here.

9) Cardiovascular Fitness

Agility is a sport with a lot of running and our dogs will need excellent cardiovascular fitness to handle the demands of this sport whether it be for training or competing. Our dogs use two different cardio systems when completing the sport of agility. The aerobic system is your dog’s endurance system and relies on oxygen to produce energy as well as stored fats and carbohydrates in our dog’s bodies. This system is relied on for endurance during an hour agility class, weekend event or seminar/workshop. The anaerobic system produces energy at a very high rate but only for a short period of time. This system does not require oxygen and is the system that is relied on for the sprinting bursts required in an agility run. An agility dog will require exceptional cardio fitness in BOTH systems to excel at this sport. If fatigue kicks in early from being deconditioned, it places a strain on the entire body that will then have to work harder to have to overcome this short coming. As an added bonus, a healthy heart will not only help with agility but will also provide greater overall health.

A final word...

Dog agility is a fun and great relationship building sport for both you and your dog! However, if you plan to train or compete in the sport, you’ll have to make sure your dog can meet the physical demands. This will take time! Remember, Rome wasn’t built in a day and the more you can do to lay a solid foundation of general fitness, and training of skills the better prepared your dog will be for this sport. In this sport, there are many things out of our control, especially when competing at a trial or event. This might include the weather, the equipment used, the terrain a course is run on, or the design of a course or sequence. The good news is there are still many things in our control that we can do to maximize our dog’s safety, performance, and longevity in the sport. One of the biggest things we can control in the sport is our dog’s physical preparation for agility.

I want you to think critically about your agility dog. Can you identify any physical requirements for the sport of agility that your dog could use some improvement in? Do they struggle with collecting and slowing down? Do they have any strength deficits that are affecting their overall performance (e.g. slow course times, less power from the hind end)? These questions are important to reflect on. By understanding areas of weakness in your dog, you can develop and formulate a plan of action to improve both your skill training and conditioning program. We are only as good as our weakness link!! It is never too late to put a plan together, but step number 1 is starting to identify what might need to be worked on!! In Part Two of our agility sport breakdown, we’ll take a look at some of these potential injuries that can occur while playing in agility. If you would like to be notified when our next blog is released and never miss another blog again join our mailing list below! Does your dog train and compete in the sport of agility? Let us know in the comments! Sources

Bosse, Christian. Power Training vs Strength Training – what is the difference between Strength Training and Power Training? Available from: https://christianbosse.com/power-training-vs-strength-training-what-is-the-difference/

Mitchell, T (2017). How to be a Concept Dog Trainer. Westline Publishing Limited, United Kingdom. Pastore C, Pirrone F, Balzarotti F, Faustini M, Pierantoni L, Albertini M. Evaluation of physiological and behavioral stress-dependent parameters in agility dogs. Journal of veterinary behavior. 2011;6(3):188-194. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2011.01.001 Pfau T, Garland de Rivaz A, Brighton S, Weller R. Kinetics of jump landing in agility dogs. The veterinary journal (1997). 2011;190(2):278-283. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.10.008 Zink, Chris. “The Agility Advantage: Health and Fitness for the Canine Athlete.” Clean Run Productions (2018).

3 Comments

Debbie Durno

9/2/2021 04:40:55 pm

A very in depth, detailed and informative article. Thanks Carolyn for your excellent information.

Reply

Jo Ann Caperna-Ford

1/27/2022 02:09:37 pm

Hi Carolyn ... a great article. I look forward to the remaining parts. Im not clear on which muscles are the stabilizers. " The stabilizer muscles, as the name would imply, help to support or “stabilize” the body."

Reply

Carolyn McIntyre

1/28/2022 08:13:50 am

Hi Jo Ann!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCarolyn McIntyre Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed