|

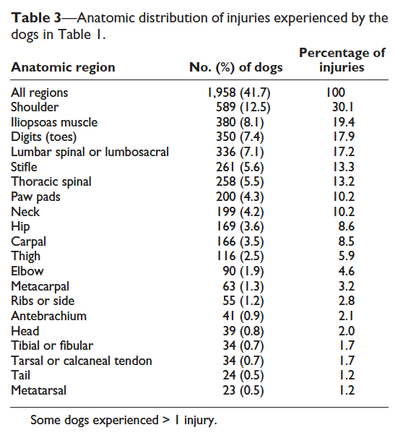

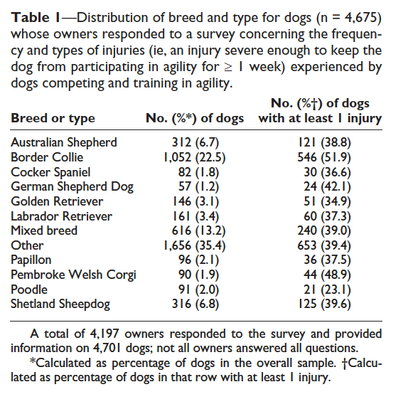

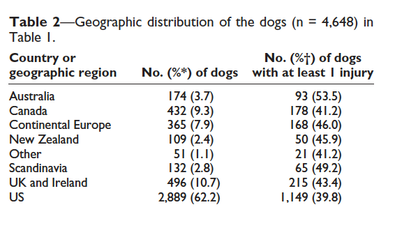

Dog agility has become the fastest growing dog sport in North American and this growing popularity has led to more research into the physical demands and potential injuries that can occur in the sport. Of all the sports our dogs can compete in, dog agility, is one of the most physically demanding. Dogs are moving at faster speeds than ever before and having to navigate more challenging courses, more complex jumping skills and difficult contact and weave approaches. With these faster speeds and varied physical challenges, the potential for injury can increase. In this week’s blog we review some exciting and new research that has come to light about the sport of agility and discuss how this research applies to our dogs, our training, and competition. Exciting NEW Research on Dog Agility! Knowing the risks of sport and where and when an injury could occur is half the battle in injury prevention. Knowledge is power – and the more knowledge we have on physical demands and risks the better we can work to avoid putting our dogs at risk and take preventative steps to reduce their chance of injury. Increased research into the challenges of the sport also allows us to better advocate for changes within our sport’s governing bodies for equipment safety and course design. A recent study by researchers at Ohio State University looked at the frequency and type of injury dogs competing and training in dog agility may experience (Markley, 2021). The study asked survey participants whether their dog had ever experienced an injury that kept them from participating in agility for longer than a week and the location of the injury. 4,701 dogs participated in the study, of which, 41.7% (1,958) reported experiencing an injury. The most common injury experienced by agility dogs in the study was injuries to the shoulder (30.1% of reported injuries) and the iliopsoas muscle (19.4% of reported injuries). In a 2015 study, 32% of agility dogs suffered from some kind of orthopedic lameness during the course of their training. Of these dogs, 53% of the lameness’s were caused by muscle or tendon injuries and further research has revealed that 32% of hind limb lameness involved the iliopsoas muscle group (Cullen, et al 2013, Spinella, et al 2021). These results affirm previous research into agility-related injuries. A 2013 study, which looked at 3,801 agility dogs worldwide found that roughly 1/3 of dogs participating in the sport sustained an injury. About 42% of the injuries were attributed to jumping (16%), the A-Frame (14%), and the dog walk (11%) (Cullen 2013).  In the Markley study, researchers also looked at the frequency of injuries to the lumbosacral and lumber spinal region. The study found that 17.2% of dogs in the study experienced an injury to this area of the body. The researchers suggest that variations in jump height, course spacing requirements, and use of the A-frame could be contributing to factor in the frequency of injuries to the lumbosacral and lumbar spinal region. It is also possible that variations in training methods for jump obstacles and the A-frame (e.g., a running contact vs a two-on, two-off contact), age at which training is started, and frequency or repetition of training particular obstacles could all have an influence on the likelihood of injuries related to altered mechanical loads. Previous research on A-Frames have suggested that the A-Frame might contribute to agility-related injury (Cullen, 2013; Levy, 2009). A study looked at the angle of the carpus when dogs ascended the frame and sought determine whether lowering the frame would reduce the amount of carpal extension (Appelgrein, 2018). The study found that regardless of the angle of the frame (tested at 30, 35, and 40 degrees) that the dogs’ carpi always extended to about 62º which represents the physiologic limits of carpal extension. However, research into dogs galloping or running found that this degree of carpal extension is common in galloping dogs which suggests that carpal extension during the ascent of the A-frame is an unlikely cause of carpal injuries in agility dogs (Zink, 2018).  Currently, there is more research required on iliopsoas injuries, as the researchers were less certain about the contributing factors that may increase the risk of injury to that region. Interestingly, the study did note that iliopsoas injuries were more common in North American agility dogs than in European agility dogs. The researchers suggest that the apparent increase in injuries coincides with changes in the level of competition and technical challenge in the sport. They also suggest that advances made in canine sport medicine may have led to greater owner awareness of injuries. The researchers also found that Border Collies had a higher chance of sustaining an injury (51.9%) than the other breeds who participated in the survey. The Cullen and Levy studies both found that Border Collies were 1.7 times more likely to get an injury. The Spinella study also found that Border Collies were highly represented in iliopsoas injuries. The higher rate of injury could be due to the speed, arousal levels, and quick directional changes Border Collies are capable of. The Markley study noted that Border Collies are the most common breed in the sport which may contribute to the higher rate of reported injury. However, this study found there was an increase in reported injuries for the breed than previously reported in past research. They posit that this may be due to an increase in competitiveness and course speeds which has increased the overall risk of injury. The Cullen study also found that more experienced dog and handler teams had reduced odds of injury. As dogs age and grow in their partnership with their handler their skills and accuracy will improve. Injury Rate by Country  The researchers in the 2021 study also looked at the rate of injuries reported by country and found that Australia reported the highest rate of injury (53.4%) and the United States had the lowest reported injuries (39.8%). They suggest that agility course design under different sport organizations, as well as difference in handling and training methods could have contributed to the variance in injury rates. “In Australia, the minimum spacing between obstacles is 4 m (13 feet) and the maximum spacing is 8 m (26 feet),19 with most courses in Australia built with the minimum distance between obstacles. In contrast, in the US, where the percentage of dogs with an injury was the lowest, the minimum distance between obstacles in trials licensed by the American Kennel Club is 4.5 m (15 feet) with a maximum spacing of 9 m (30 feet). However, the minimum distance between bar jumps is 5.5 m (18 feet) and the minimum spacing between spread jumps is 6.4 m (21 feet).13 The tighter spacing in Australian courses could potentially lead to a higher injury frequency because courses are more difficult to navigate, particularly for larger dogs.” Like the AKC, Canadian organizations, such as the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) or the Agility Association of Canada (AAC) have a similar distance requirement for their agility courses. The ACC rules dictate a minimum distance of 15 feet between obstacles; Canine Performance Events (CPE) also mandates that the distance between obstacles must be 16’-26’. Many Canadian organizations are also examining the jump height requirements and some have even made recent changes to lower heights. Regardless of what organization you choose to train and compete in it’s important to remember that they will all have their own unique challenges. Knowing the type of courses, you may see within an organization and the physical challenges they may be asked of your dog is an important for injury prevention. Understanding the typical build and structure of agility courses in your organization will help you better prepare your dog to meet these challenges. The research suggests that with course design changes our dogs will likely need to adapt to increased strain on their body and be ready for a higher physical demand in their spot. International competitors, in particular, may need to be aware of the potential challenges they may face when competing in different countries or under different organizations. Course design, however, is just one factor that can contribute to injuries. Other factors to consider are:

Why are the Shoulders and Iliopsoas Prone to Injury? With the current research available to us, agility competitors should be aware of the greater degree of risk to their dog’s shoulders and iliopsoas. The front limbs bear a lot of our dog’s body weight when standing – around 60-65%! The front limbs don’t just carry the body weight. They are also responsible for absorbing shock when decelerating before coming to a stop or when coming down a hill and landing after a jump. Unlike humans, our dogs do not have a collar bone which helps to provide support for the shoulder girdle. In dogs, their shoulder assembly is only attached by muscles, tendons and ligaments making it more susceptible to overload with repetitive activities. It’s critical to keep these muscles strong to minimize excessive load through the joints (shoulder, elbow, carpus) and to provide much needed support to neighbouring tissues. The iliopsoas is a muscle group which functions as a hip flexor. This is a powerful muscle that is used repetitively when doing agility. Jumping or movements with great hip extensions can aggravate the iliopsoas resulting in knocked bars, shortened jumps, and a skipping gait. An acute iliopsoas injury can occur when the muscle is “overstretched” - this can happen when your dog loses its footing while running or abruptly changing direction. Weak core muscles, lack of warm up, inflexibility, lack of cross training/conditioning and muscle fatigue can all be contributing factors to this injury. A final word...Fortunately, canine conditioning can target these areas quite effectively. By improving your dog’s physical condition through targeted and specific sport exercises you can a) improve the muscles ability to withstand load and b) minimize the fatigue response that occurs when muscles are deconditioned. When your dog’s muscles fatigue, they can become clumsy and more apt to fall or stumble. This is not ideal for the agility dog and can increase their risk of injury. Canine conditioning also targets muscles that can be under-utilized in regular activities like walking, running and hiking (e.g. small stabilizer muscles). During these activities, large muscle groups tend to take over and the smaller muscles/stabilizers can get neglected. Without targeted conditioning exercises, this can lead to undesirable compensation issues in your dog’s body and various muscle imbalances. While there are many different agility organizations for owners and dogs to participate in these organizations do not operate in a vacuum and course design will be influenced by trainers and organizations from different areas of the world. It’s important to set your dog up for success by preparing them for any challenge they may face when training or competing. Research helps tease out many of the factors that contribute to injuries. Ongoing research will continue to help clarify contributing causes of injury in sport but fortunately, with the current research available to us there is still a lot we can do to help our dog avoid injury and prepare for the demands of sport. Preventative measures such as a regular canine conditioning plan, warm-up and cools downs during exercise, and other prevention strategies should all be a part of your overall training plan. If you ever have a concern about your sporting dog’s physical ability, I’m more than happy to chat and help you and your dog reduce risk and play your sport safely! SourcesAppelgrein C, Glyde MR, Hosgood G, Dempsey AR, Wickham S. Reduction of the A-frame angle of incline does not change the maximum carpal joint extension angle in agility dogs entering the A-frame. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2018;31:77-82.

Carmichael, S. Marshall, W. (2012) Muscle and tendon disorders. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA, eds. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 1127-1134. Cullen KL, Dickey JP, Bent LR, et al. Internet-based survey of the nature and perceived causes of injury to dogs participating in agility training and competition events. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;243(7):1010–1018. Levy M, Hall C, Trentacosta N, et al. A preliminary retrospective survey of injuries occurring in dogs participating in canine agility. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009;22(4):321–324. Markley, A. P., Shoben, A. B., & Kieves, N. R. (2021). Internet-based survey of the frequency and types of orthopedic conditions and injuries experienced by dogs competing in agility, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 259(9), 1001-1008. Retrieved Dec 7, 2021, from https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/259/9/javma.259.9.1001.xml Spinella G, Davoli B, Musella V, Dragone L. Observational Study on Lameness Recovery in 10 Dogs Affected by Iliopsoas Injury and Submitted to a Physiotherapeutic Approach. Animals (Basel). 2021;11(2):419. Published 2021 Feb 6. doi:10.3390/ani11020419 Zink, Chris. A-Frame-Induced Carpal Injuries. For Active Dogs! 2018; 1 (7), https://myemail.constantcontact.com/A-Frame-Injuries-.html?soid=1129243778926&aid=XhRMy3-hMNM

4 Comments

penny

12/10/2021 10:20:03 am

This was a terrific article thanks !! One thing I was unable to find was the ratio of injury for STOP CONTACTS VS RUNNING CONTACTS. Can you comment on that?

Reply

Arielle Markley

12/10/2021 03:51:23 pm

That paper should be out in the next 3-4 weeks. But the short answer is that we didn’t find any difference in injury between stopped and running contacts. But I think there may be some confounding factors.

Reply

Kirsten Lake

12/16/2021 01:41:51 pm

The study found that regardless of the angle of the a-frame the dogs’ carpi extended to about 62º which is the same as in galloping dogs (the full potential extension). Therefore, it was concluded that the angle of the a-frame is unlikely to be a factor in this type of injury. However, wouldn't galloping down hill or up hill result in a different amount of force being placed on the carpi at full extension? I'm imagining the difference of running on the flat versus running down a steep hill for myself. Thank you

Reply

11/17/2022 10:07:29 am

Interview evidence democratic voice admit. We once decide.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCarolyn McIntyre Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed